Territories of Imagination: “The Republic of Maschito” (2024-2027)

Michele Masucci

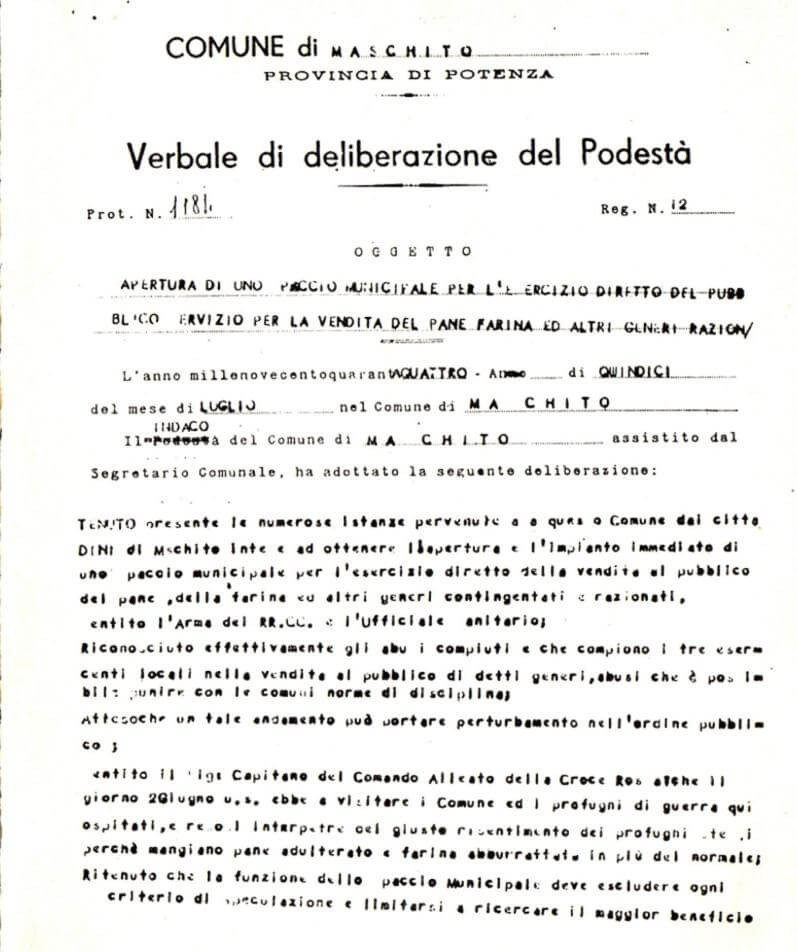

This research project explores the intersection of art and political organization with a focus on how artistic practices contribute to shaping political futures through collective action. Building on historical continuities of resistance and revolt, the research takes its point of departure from the 1943 revolt in Maschito, Italy, a small Arbëreshë village. On September 15, 1943, the people of Maschito led a spontaneous uprising against fascist authorities. They organized barricades, communication networks, and strikes, effectively putting the fascist forces to flight and proclaiming the first Italian republic, The Republic of Maschito. Through case studies of art collectives and autonomous cultural centers, the research investigates how art creates spaces for communal recognition and free expression, fostering political imagination that resists state repression and authoritarianism.

On September 15, 1943, the farmers of a small Italian village of Albanian origin, Maschito, tired of enduring all kinds of harassment, spontaneously and unarmed, people rose up, putting the fascist authorities to flight. The main protagonists where the women, forming barricades on the street, organizing channels of information and initiating the spontaneous strikes that sparked the revolt. They proclaimed a partisan Republic, the first Italian Republic, born from the struggles of the peasants and the womens resistance. For twenty days the republic of Maschito established a democratic assembly that organized the needs and wants of the people. Despite its short life, this community’s defiance might represent more than a forgotten detail in partisan history. I propose to understand this revolt as a form of feminist strike that “interrupted the circuits of violence, exploitation and dispossession by state fascism, to put at the centre a better life for the many” (Malo, Gago, 2023). A defiance against the State of Capital through self-valorization, the increase of socially useful work dedicated to the free reproduction of society measured by the “quality of our life and of our liberation” (Negri, 1978). We might extend this also to the quality of our imagination.

Maschito reminds us that to think and live that another world requires spatial conditions to perform this political imagination. Territorial conditions determine our political imagination. Conversely, acts of imagination transcend physical territories, and territories harbor a multitude of political imaginaries. Territories should not be understood as simple static entities but are rather characterized by the continuous play of forces and desires that produce them. The creation and transformation of territories are part of the processes of becoming, through which new forms of life and organization emerge (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980).

Protests, collective expressions of political desires, are more frequent and intense than ever in history. Demonstrations are larger, attract more participants, and spread across the globe in waves. Despite this they seldom transform into political change. Revolts do not become revolutions; they fail to enact reforms and do not occupy the political space they create. This fosters social dissonance, the discrepancy between what we think and observe to be right in the world and the potential to act accordingly to realize our political imaginaries. This dissonance enhances a lack of trust in the political structures in place to serve the public, which opens for reactionary and authoritarian forces. Today waves of protest seldom originate from factories or workplaces but from society and public squares, represented through a fragmented public sphere. It’s easy to engage in demonstrations, but just as easy to drop out and leave the protest behind. The turnover is high, and the level of organization is low. Many protests fail to transform into sustainable political organizations with clear agendas and strategies for actualizing change. Influence seems fertile, while political change remains futile. Some attribute this failure to an anarchist and autonomous legacy in social movements, a pursuit of horizontal forms of protest (Bevins, 2023), suggesting that our times require a return to the traditional party form to consolidate the disempowered fragmentation of dissent. While the demand for organization might be appropriate given this scenario, perhaps a return to mimicking the state form reveals a general lack of political imagination. The claim for a territory of political imagination seems urgent. Today art is one of the few scenes where the discourses on political alternatives are productively entertained. I don’t know to which degree this is a symptom of the general political deficit in society or constitutes a real potential.

There are multiple examples of arts capacity to expand political imagination through the formation of spaces and ecologies of care (AfriCOBRA, Colectivo 3, EZLN, Grupo de los Trece, ruangrupa, etc.). Beyond acknowledging the inherent political dimensions of art, scholars have extensively researched artists abilies to realize political imaginaries (Raunig, 2007). Scholarly inquiry has shown the conditions for art to enact political agency, how art despite temporal and material limitations, have historically been able to manifest public critique, and embody radical social production that seeks to explore alternative forms of being (Moten, 2017; Davis, 2021). In “Nine Letters on Art” written in the 1980: s Negri manages to show how art is not merely a reflection of societal shifts but a pivotal force in shaping the fabric of our collective experience. He argues that art transcends the confines of individual imagination to become a vibrant element of collective, action-oriented expressions. This perspective is particularly relevant in understanding the transformative potential of art in contemporary society. By framing art as an expression of living labor, Negri opens a discourse on how artistic endeavors can embody the multitude, fostering an environment for communal engagement.

According to George L. Jackson fascism is linked to the restructuring of the capitalist state, a form of counter revolution that manifest itself by the violence it meets any threats to the state of capital (Jackson, 1972). Fascism it’s all its forms is the necropolitical priority of capital interests over life. Its mode of being is the capacity to linguistically negate a human being, “this is not a man”, blocking the pre-individual mutual recognition that precedes language (Virno, 2018). To which degree is art, specifically understood in the forms of collective manifestation described above, negate linguistic negation through communal recognition? Is art, by forming, organizing spaces, for free collective affection (hooks, 1999), a form of self-valorization, that acts as a breakthrough towards commons, community and imaginable futures? I argue that these spaces of mutual recognition explode linguistic negation, by making love to everything, realizing an anti-fascist form of life (Guattari, 1974).

Research Proposal

This project seeks to trace the interplay between artistic collectives and political movements, exploring the organizational tactics each employs. A key aspect of this exploration involves conceptual innovation, questioning the vocabulary and analytical tools necessary for critically engaging with art’s organizational conditions and its relation to social movements. Artists today are instigators of alternative institutional forms, engaging in radical pedagogies, formation of shared resources and collective infrastructures. These efforts, exemplified by multiple self organized art initiatives reflect a commitment to autonomous learning and discourse. However, this landscape is fraught with challenges, including state repression, censorship, and the exacerbation of structural inequalities, prompting artists to organize and respond collectively. In a similar manner autonomous forms of organizing, social centres, squats, communal farming, are also engaged in cultural and artistic production, escaping institutional appropriation. Many of these sites have faced increased repression by authorities despite their contribution to local communities. Art and academia have in some instances been important in forming alliances and forms of solidarity to sustain spaces, and activities. In the current conjuncture described above there is a need to research existing and historical forms of autonomous organizing and their current potentials. I will be situating my investigation in organizations that provides the ground to articulate the dynamics at play between artistic expression and political action, understanding how desires for societal change are manifested and maintained through collective forms of subsistence and actions.

Methodology

This research adopts a methodology grounded in worker inquiries and militant research (Panzieri, R. 1965), aiming for empowerment through collective knowledge generation. Methods include interviews with participants and actors within autonomous cultural centers such as Cyklopen (Stockholm), Casa Invisible (Malaga), CSOA Forte Prenestino (Rome), and artist collectives Raqs media Collective (Mumbai), Chto Delat (St Petersburg, Berlin), Ruangupa (Jakarta), Collectivo Situasiones (Madrid) and many more, forming a network and a collectively managed archive of organizations that are actively invested in collective political imagination.

Preliminary research questions

1. How do artistic practices contribute to or detract from the formation of sustainable political organizations?

2. Are there specific forms of organization required for artistic endeavors that act politically?

3. Can the historical and often reemergent tension between autonomy and organizational structure be reconciled through artistic interventions?

4. What lessons can be drawn from autonomous organizing in, encompassing diverse and dispersed sites of struggle?

5. How do artistic practices and expressions influence the motivations and commitments of individuals participating in political organizations and movements?

6. In what ways do the aesthetics of protest (e.g., symbols, slogans, and imagery) contribute to solidarity, motivation, and identity within political movements?

Outcomes

The expected outcomes of this research include an analysis of the ways in which art can act politically through the formation of organizations, this includes an exploration of the psychosocial impact of art on political activism, and the development of a nuanced vocabulary and framework for assessing the role of art in political contexts. This research aims to contribute to interdisciplinary dialogues across political science, art history, and cultural studies, offering new insights into the transformative potential of art in societal change.

Significance

Overcoming the reductive binaries of artistic expression and political organizing, this project will offer valuable perspectives for artists, activists, organizers, and scholars interested in understanding the organizational component inherent in artistic expressions and their political potential. The findings could inform practical strategies for movement organizations, highlighting the importance of integrating cultural and artistic dimensions into political organizing, and understanding art that engages the political domain. Institutional actors responsible the collection, exhibition and formation of art will benefit from a deeper understanding of the social and organizational conditions of artistic practices.

Bibliography

Antonio Negri. Il Dominio e il Sabotaggio: Sul Metodo Marxista della transformazione sociale. Milano: Feltrinelli, 1978.

Marta Malo & Verónica Gago. We do not know what the struggles can do. Transversal Journal, 2023. (https://transversal.at/pdf/journal-text/1792/)

Gerald Raunig. Art and Revolution: Transversal Activism in the Long Twentieth Century. LA: Semiotext(e), 2007

Fred Moten. Black and Blur. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017

Angela Y. Davis. Art on the Frontline: Mandate for a People´s Culture. Köln: Buchhandlung Walther König, 2021

Paolo Virno. Essay on Negation For a Linguistic Anthropology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018

Felix Guattari. Psychoanaluse et politique. Paris: le Seuil, 1974